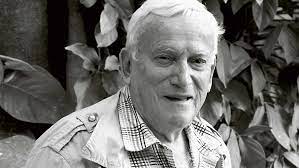

La Grita (Venezuela), 1928

By Roberto Segre

Beginning oil exploration in the 1920s, the Venezuelan economy became dependent on the enormous resources produced by “black gold.” This resulted in the depopulation of rural areas and a progressive increase in the urban population throughout the 20th century, particularly among low-income social strata. As the housing problem intensified, the state heavily invested in massive housing complexes, disregarding typological or technical solutions that would adapt to the population’s desires or economize on materials and labor. Hence the exceptional nature of the proposals and research carried out by José Fructoso Vivas Vivas on the subject of popular housing.

A restless and passionate student, he had the opportunity to collaborate with Oscar Niemeyer during his stay in Caracas (1954) to design the inverted pyramid of the Museum of Modern Art. Newly graduated from the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) in 1955, that same year he won first prize in the competition for the design and construction of the Táchira Club, whose main space was covered with a thin layer of reinforced concrete. His passion for advanced technologies led him to connect with Spanish engineer Eduardo Torroja, who advised him on the project. The principle of the lightweight membrane reappeared in the church of Zapara (1960). Identified with urban housing

low-cost, built by users with local materials, he developed the attributes of a “populist architecture,” which he called “trees to live in.” The proposal consisted of prioritizing the bioclimatic character of the housing unit through natural ventilation in spaces defined by light and interchangeable partitions, the use of steel structural elements that would allow the grouping of units in space, and the creation of “green” terraces intended for self-cultivation in the urban context. Thus, the rigid apartment blocks were overcome by an articulation between the persistence of the individual unit and its integration into a free and changing organization. Although this spatial image had only a partial application in the Corpoven housing complex in Lechería (1995), the experimentation with the free and transparent character of the unit—strongly ventilated, with interior greenery and wooden frameworks of movable panels—was present in several houses built in the 1970s and 1980s: his own residence; that of Aldo Riccio in Barquisimeto; those of Homero Marín and Eduardo Loaiza in Caracas; and that of Raúl Estévez in Mérida.

José Fructoso Vivas Vivas tried to realize his ideas in Cuba—where he lived between 1966 and 1968—designing lightweight construction systems, modular equipment, and nurseries, but the influence of heavy Soviet prefabricated structures dominated the Cuban architectural scene, excluding the architect’s innovative proposals. In 1980, he organized the “Carlos Aponte” brigade of professors and forty UCV students who lived for a year in Nicaragua to collaborate in the reconstruction of Managua, building the church and the plaza in the Villa Venezuela neighborhood.

His system of metal frames applied to houses in poor neighborhoods of Caracas (Niño Jesús) was awarded at the Second Architecture Biennial of Venezuela (1979). In 1987, he received the National Architecture Award. The project of the Venezuelan Pavilion at the Hannover World Fair (2000) attracted attention, defined by gigantic metal petals of an orchid that opened and closed according to the intensity of ambient light, supported by a central column representing a Tepuy (a mountain typical of the Guayana Massif).

In 2014, he received the Ibero-American Award for his professional career of more than sixty years in architecture.