Nova York (Estados Unidos), 1936

By Ángel G. Quintero Rivera

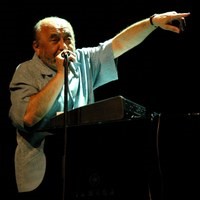

The New York-born Latino (Nuyorican) Eddie Palmieri began his musical life during the intense years of the great Puerto Rican migration to New York. Between the ages of fourteen and seventeen, he entertained local parties with a small ensemble, and by the age of 21, he was recruited as the pianist for the most renowned Latin big band at the time, the Tito Rodríguez Orchestra. Due to his experimental nature, he left the prestigious institution of Latin music to form his first professional group, which he named La Perfecta, a clear reference to the meticulousness of his “craftsmanship.” Like many other musicians in the Latino-Caribbean tradition, he combined the roles of instrumentalist, director, composer, producer, and arranger. His older brother—also an extraordinary pianist—Charlie Palmieri (1927-1988), who had introduced new elements to the charanga format (forming La Duboney with Dominican flutist Johnny Pacheco), named Eddie’s band “Trombanga” due to the prominence of trombones, a feature that would come to define the salsa sound. The trombonists were New York Jew Barry Rogers and Brazilian João Donato, who was later replaced by another Brazilian, José Rodrigues. In 1966, La Perfecta recorded El sonido nuevo with jazz vibraphonist Cal Tjader, marking the first major fusion of salsa and jazz.

Salsa Discourse

In 1969, Eddie Palmieri produced Justicia, one of the first salsa classics. Unlike the typical popular music productions of the time, the album was not a mere compilation of songs but a discourse woven throughout the tracks, making it a true opus. The album begins with the title track, Justicia, in which Palmieri expresses the characteristic that would define salsa: a free combination of various Caribbean rhythms and musical forms, evoking many geographies and times from its complex history. The dominant rhythm in Justicia is guaracha, one of the earliest urban genres from the Caribbean (originating when it was still predominantly rural). Palmieri’s work begins with the oldest urban sound of its predecessors and, over this sonic base, the lyrics call out for justice with optimism for Puerto Ricans and African Americans.

Like all the compositions on the album, this opening track includes extraordinary instrumental improvisations—descargas—inspired by the best traditions of jazz. The trumpet descarga alludes to the most famous social bolero by Puerto Rican composer Rafael Hernández, Lamento borincano (1929), composed during the Great Depression when he was living as an immigrant worker in New York. The LP then weaves together traditional Latin-Caribbean music with the new sounds of Latin jazz, blending African American music with a wide range of forms, styles, tempos, and rhythms. Palmieri incorporated interludes from the song Somewhere from the musical West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein. After the first interlude, the second song is a bolero by Rafael Hernández, Amor ciego, which, as is typical in this genre, addresses the theme of separation. The song might not have much appeal if not for how Palmieri sprinkles traditional sonorities with frequent avant-garde dissonant chords and his innovative descargas. The third track evokes another type of traditional Caribbean sound: a guajira by Cuban Ignacio Piñero. After the second interlude, the album moves toward modernity with “My Spiritual Indian,” a composition by Palmieri that refers to the early centuries of Caribbean formation. It’s a full descarga that evokes the meeting of Native Americans and enslaved African escapees. The composition mixes scales identified with indigenous sounds and Afro-Caribbean rhythms. The modern harmonies and improvisations mark it as a pioneering work in Latin jazz.

The second side of the album opens with a Palmieri composition in English inspired by the hip-hop culture of New York’s Black neighborhoods, which revisits the theme of justice that had opened the first side in Spanish. Palmieri composed all the songs in Spanish that reflect Afro-Caribbean roots as salsa. The song Everything is Everything is in English because it deals with African American music. (The other English-language song on the album is Somewhere, which in the original West Side Story is sung in a duet by an Italian-American and a Puerto Rican descendant.) With the sound of the ghetto enriched by jazz—sound that transcended from that point onward—Palmieri gives the lyrics a “third-world” scope in their demand for social justice and his utopia for a new, more solidaristic form of life.

After another interlude leading into the final Somewhere, the orchestra embarks on a long descarga full of complex bebop polyrhythms from the most advanced jazz of the time, “Verdict on Judge Street,” also composed by Palmieri. And, transforming the famous modern romantic utopia from the musical with jazz modulations and a marked Puerto Rican accent, the album ends by recalling the most universal and yet most concrete of utopias, a place and time to live: Somewhere, a place for us, someday, a time for us…

Awards

Since that time, Palmieri has continued to produce excellent works, both in salsa and jazz. When the Grammy introduced the Latin music category, Palmieri received the award in 1975 and 1976, and he was awarded five more times, with ten nominations. At the end of the 20th century, the Grammy established a new category for Latin Jazz, for which Palmieri was nominated on two additional occasions. His 1996 album Vortex, where he plays Beethoven’s Minuet in G in Latin jazz style, is considered one of the best Latin American musical productions of all time. In 2006, he won another Grammy for the album Listen Here, and the following year, another Grammy for Simpático. In 2013, he received the most prestigious award in American jazz, the NEA Jazz Master Award, and in September of that year, he released the album Sabiduría.