Born in the Buenos Aires locality of Chascomús on March 12, 1927, he is the first of six children of Serafín Raúl Alfonsín Ochoa and Ana María Foulkes. At 13, he entered the General San Martín Military Lyceum and later studied law at the National University of La Plata. In 1946, he began his political career by joining the Movement of Intransigence and Renovation of the Radical Civic Union (UCR), which brought together a new generation of radicals, including future president Arturo Frondizi (1958-1962) and leader Ricardo Balbín. In 1949, he married María Lorenza Barreneche, and they had six children. Between 1950 and 1956, he held various important positions in his party.

Born in the Buenos Aires locality of Chascomús on March 12, 1927, he is the first of six children of Serafín Raúl Alfonsín Ochoa and Ana María Foulkes. At 13, he entered the General San Martín Military Lyceum and later studied law at the National University of La Plata. In 1946, he began his political career by joining the Movement of Intransigence and Renovation of the Radical Civic Union (UCR), which brought together a new generation of radicals, including future president Arturo Frondizi (1958-1962) and leader Ricardo Balbín. In 1949, he married María Lorenza Barreneche, and they had six children. Between 1950 and 1956, he held various important positions in his party.

In 1957, when the UCR split into UCR del Pueblo (UCRP) and UCR Intransigente, the former led by Balbín and the latter by Frondizi, Alfonsín aligned with the more conservative UCRP. In 1958, he became a provincial deputy for UCRP and was re-elected several times until 1963. After the military coup of 1966, he publicly opposed the dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía, for which he was imprisoned. As political parties had been dissolved and party activity was banned, he continued his advocacy through journalism. In the magazine Inédito, he published numerous critical articles on the Argentine Revolution. After Onganía’s fall, he clashed with Balbín and rallied the youth sectors of radicalism around him. Between 1971 and 1972, he allied with leader Conrado Storani, forming the Renovating Movement, which in 1973 became the Movement of Renovation and Change, deeply critical of the Peronist government. By 1975, during Isabelita Perón’s government (1974-1976), he was part of the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights. During the years of the military dictatorship (1976-1983), he engaged in clandestine activities from the magazine Propuesta y Control. In mid-1981, he participated in the Multipartidaria, a call from political parties to pressure the dictatorship towards democratic opening. After the Malvinas War and with the fall of the military government, elections were called, and Alfonsín began his journey toward the presidency, supported by the youth and student movement.

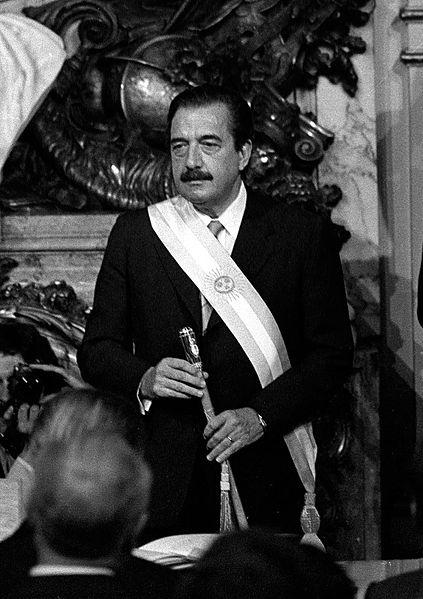

On October 30, 1983, he won the elections with over 52% of the votes. He took office on December 10, Universal Human Rights Day. In the field of diplomacy, after seven years of dictatorship and with the Malvinas War still fresh in memory, the Alfonsín government sought to reintegrate Argentina into the international arena through strong presence in Latin American forums. This included acceptance of the papal ruling in the conflict with Chile over the Beagle Channel – which the public supported through a plebiscite – entry into the Cartagena Consensus due to the external debt crisis, and negotiations with Brazil and Uruguay that preceded the creation of Mercosur.

The most contentious issue for the radical government was the prosecution of state terrorism, the crimes against humanity committed by the military between 1976 and 1983. To address this, Alfonsín created the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Conadep), which, chaired by writer Ernesto Sabato, produced a detailed report on the disappeared, dead, and tortured during the dictatorship in the 340 clandestine detention centers that operated across the country. The report, titled Nunca más, and the Trial of the Military Juntas in 1985 demonstrated that there was a systematic plan to exterminate opponents in the country. In the trial, five of the nine accused military personnel were convicted.

Facing resistance and pressures from the Armed Forces – which included two military uprisings – Alfonsín’s government yielded. Under the banner of achieving “national reconciliation,” his party and he himself promoted, in agreement with Peronism, the passage of the laws of Obedience Due and Final Point, which amnestied over two thousand military personnel accused of human rights violations, except for those who committed the crime of stealing babies from the disappeared.

Alfonsín’s relationship with the unions was problematic. The General Confederation of Labor (CGT) carried out fourteen national strikes, adding to the social unrest caused by the economic situation in the country. In February 1989, during the electoral campaign for the presidential succession, a severe hyperinflationary wave began. In the following weeks, there were looting of shops and supermarkets. In the face of the widespread chaos, Alfonsín resigned five months before the end of his term and handed over power to Justicialist Carlos Saúl Menem, who had won the elections. From the leadership of the main opposition party, he became the driving force behind the agreement with Justicialism known as the “Olivos Pact,” which allowed Menem’s presidential re-election and enabled the constitutional reform of 1994. In 1997, together with Carlos Chacho Álvarez, leader of Frepaso, he founded the Alliance, which won the elections in 1999 and brought Fernando de la Rúa to the presidency. Between 1980 and 2004, he published several books, including La cuestión argentina, Una propuesta para la transición a la democracia, Alfonsín responde, Democracia y consenso, and Memoria política.

He currently integrates important international political organizations: the Socialist International; the Interaction Council, which brings together former presidents of various countries; the South American Peace Commission; the Interamerican Dialogue; the Advisory Committee of the PAX Institute; and the Latin American Center for Globalization. Throughout his long political life, he received numerous awards and honors, including the Prince of Asturias Award. He holds honorary doctorates from several universities in America and Europe.

Content updated on 07/03/2017 14:19