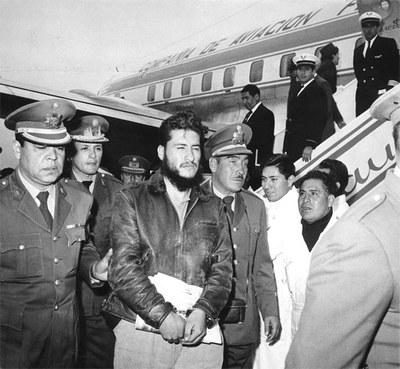

With the Cuban Revolution of 1959, guerrilla “focos” were reproduced as instruments of transformation throughout Latin America in the 1960s. The experience of Hugo Blanco and his peasant “unions” was very different: in this case, the organization of the people was the premise for mobilization. Such an approach was not unfounded, judging by the results obtained and the multiplication of unions in the southern Andes. The landowners could control all the land they wanted, but its value depended on the unpaid labor of the indigenous people. If these workers adhered to the strikes organized by their unions, they would have the power to trigger a severe agrarian crisis. In response to the increased repression of peasant movements, Blanco and the Chaupimayo Union took up arms through a guerrilla column. In May 1963, the group was dismantled, and Blanco was captured and sentenced to 25 years in prison. In 1970, the government of Juan Velasco Alvarado granted him amnesty, and in 1971 he was deported. He lived in Mexico, Sweden, Argentina, and Chile until returning to Peru in 1975 and rejoining political life. In 1976, after a popular protest against the new military regime of Francisco Morales Bermúdez, Blanco was exiled once again. He returned in 1978 and joined the Constituent Assembly. During the 1980s, between 1980 and 1985, he was elected national deputy by the Izquierda Unida coalition and served as a senator of the Republic until Alberto Fujimori’s coup in 1992. In the 1990s, he defended the interests of the peasants in Cuzco, proposing the legalization of coca leaf cultivation and the purchase of 100% of the production by industrialized countries. This would be the only means of gaining the support of the peasants in the fight against drug trafficking.

Despite the persecutions, from the beginning, Hugo Blanco’s actions precipitated the implementation of agrarian reform in Peru. Before the Peruvian Army officers’ government imposed one of the most radical agrarian reforms in the region in 1969, the country’s rural landscape was dominated by both agro-industrial plantations dedicated to cotton and sugar processing, and by large traditional latifundia whose production served to maintain their staff or produce small surpluses for local and regional markets. The former were capital-intensive and generally located on the central and northern coast of Peru. The latter, the traditional haciendas, were more labor-intensive and were spread throughout the Andean region.

The daily life and exploitation imposed by the traditional hacienda owners on the workers, whether they were called serfs, settlers, tenants, or huasipungueros, were not much different from those that prevailed in medieval Europe, in the sense that they exploited the owner’s poorest lands in exchange for paying rent in labor or products. But this situation began to change in the second half of the 20th century, with population growth, the deterioration and decline of rural resources, and the allure of the big city. A wave of peasant mobilizations began, mostly by small landowners, who invaded the lands of nearby haciendas. According to them, they were “recovering” the lands because they believed that much of those lands were simply the result of dispossession imposed on the peasants by the landowners. These mobilizations went from demanding land ownership to questioning the legitimacy of the traditional agrarian order.

Not all of these mobilizations were external. There was also pressure from the settlers and serfs who worked and lived on the borders of the large latifundia. An example of this occurred in the 1960s in the valleys of La Convención and Lares, in Cuzco, an area specialized in coffee production and export. The mobilization of the region’s “tenants” was a total success, the result of the efficient organization of these producers into “unions,” due to the commitment and teachings of Hugo Blanco.

Content updated on 07/03/2017 20:59.