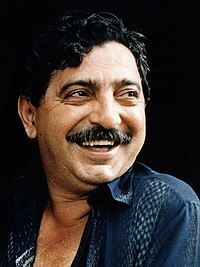

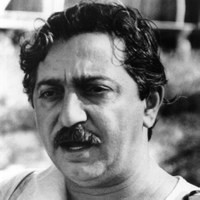

Xapurí (Brasil), 1944 – 1988

By Carlos Walter Porto-Gonçalves

The popular leader Francisco Alves Mendes Filho was born in the Porto Rico rubber plantation, in the municipality of Xapuri (Acre) on December 15, 1944. He was the son of Northeastern parents who migrated to the Amazon. From the age of eleven, he worked as a rubber tapper, sharing the common fate of those families whose children, instead of going to school, worked to extract latex. Chico Mendes had the fortune of meeting his great mentor, Fernando Euclides Távora, who taught him not only how to read and write, but also how to follow the path that would lead him to care about the future of the planet and humanity. Euclides Távora was a communist militant who actively participated in the communist uprising of 1935 in his hometown of Fortaleza and also in the 1952 Revolution in Bolivia. Returning to Brazil through Acre, Euclides Távora settled in Xapuri, where he became Chico Mendes’ mentor. The disciple often spoke with great affection of his political mentor, whom he would never see again after the 1964 coup. Education became an obsession for Chico Mendes, which he gave a very practical political meaning, believing that by learning to read and write, the rubber tapper would no longer be cheated in the accounts of the boss’s store.

In 1975, already involved with the base ecclesial communities (CEBs), he founded the first rural workers’ union in Acre, in Brasileia, with his friend Wilson Pinheiro. In March 1976, he organized the first “empate” (strike) in the Carmen Rubber Plantation. The “empate” consisted of the gathering of men, women, and children, under the leadership of the unions, to prevent deforestation of the forest, a practice that became emblematic of the rubber tapper’s struggle. In the “empates,” the rubber tappers warned the “peons” working for cattle ranchers—usually from outside Acre—that clearing the forest meant the expulsion of workers’ families. They invited the peons to join their fight by offering them “locations” and “rubber trails” to work, and firmly expelled them from their destruction camps, halting the work. The “empates” played a decisive role in consolidating the rubber tappers’ identity, and this form of resistance drew the attention of all of Brazil, especially after the murder of Wilson Pinheiro in 1980.

Chico Mendes insisted on the “empates,” mobilizing the rubber tappers, even after government authorities, in light of the impact of his resistance, started creating colonization projects. Chico Mendes rejected these projects, as they would turn the rubber tapper into a settler-farmer, confined to 50 or 100 hectares of land, which showed his clear understanding of the meaning of that government strategy, which found support even among union militants. Chico Mendes valued the rubber tapper’s way of life, which used a small plot of land next to the house to grow crops and raise small animals while collecting fruits and resins from the forest. For rubber tappers, the object of labor was not the land, but the forest. Therefore, more than land, Chico Mendes and the rubber tappers fought for the forest, and it was this firm conviction that earned him the support of his peers and brought him closer to environmentalists, a group he viewed with suspicion, as he often expressed to friends. As a communist, Chico Mendes distrusted not only environmentalists but also several emerging social movements (women, blacks, and homosexuals), which he believed divided the workers’ struggle. However, as a practical man with great capacity to subordinate principles to life without losing sight of his fight, he realized that environmentalists, by defending the forest, were important allies in his struggle, allowing the rubber tappers to break their isolation. Environmentalists, for their part, recognized the importance of the rubber tappers’ fight for forest preservation. From this alliance, Chico Mendes formulated a principle that would characterize his philosophy: “There is no defense of the forest without the people of the forest,” a principle that can well be extended to other situations of environmental defense.

Chico Mendes realized that the rubber tappers’ struggle was of global interest and, little by little, he became convinced that, in addition to the exploitation of workers, capitalism had a destructive and voracious force that needed to be combated, thus becoming one of the greatest proponents of eco-socialism. With his keen holistic perception, he rejected both narrow unionism and narrow environmentalism. In 1984, at a national meeting of rural workers, Chico Mendes defended an audacious proposal for the time: that agrarian reform should respect specific social and cultural contexts. A year later, when founding the National Rubber Tappers Council in Brasília, he was already developing, with his companions, the proposal for Extractive Reserves—a true revolution in the concept of environmental conservation units, which for the first time no longer separated man from nature. The Extractive Reserve, which Chico Mendes referred to as the rubber tappers’ agrarian reform, enshrined all the ideological principles he advocated, as, while each family had the right to use their rubber location, with their house and rubber trails, the land and the forest were for common use—a communal idea inspired by indigenous reserves. Based on this, he worked with his friend Ailton Krenak to build the Alliance of the Peoples of the Forest, uniting indigenous people and rubber tappers and reversing the history of massacres instigated by large rubber plantations and rubber barons. In this action, the profound humanistic sense of Chico Mendes’ ideology found practical meaning. It is worth noting that the Extractive Reserve proposal also included an innovative relationship between society and the State. While the formal ownership of the reserve belonged to the State (in this case, IBAMA), its management was entrusted to the community itself, with the public agency supervising the fulfillment of the usage rights contract, which established a pact between the State and the rubber tappers.

Throughout his life, Chico Mendes never stopped dedicating himself to building tools for social and political struggles, having been a national leader of the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT) and the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT), as well as the National Rubber Tappers Council. Chico Mendes’ political and moral legacy is enormous and can be seen both by intellectuals who recognize the originality of his ideas and political practices and by politicians who, both in his state and in his country, have their positions linked to the struggles he led. His work was recognized in Brazil and around the world: in 1987, he won the Global 500 Prize from the UN in London and the Medal of the Society for a Better World in New York; in 1988, he was awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

His immense belief in human capacity to overcome the contradictions of the world in which they live, organizing socially and politically, inspired a whole set of ideas and practices that view nature, with its productivity and capacity for self-organization (negentropy), and human creativity in its cultural diversity as the foundation of environmental rationality (Enrique Leff) or, as he liked to call it, a society that combines socialism with ecology.

On December 22, 1988, assassins linked to the União Democrática Ruralista ended Chico Mendes’ life, thinking they could silence the voice that, like a poronga—the instrument that rubber tappers carry on their heads to illuminate the trails when they go out, still at night, to work—continues to light the way.