La Rioja (Argentina), 1930

By María Seoane

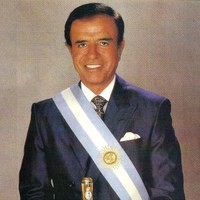

Born on July 2, 1930, in the province of La Rioja, Carlos Saúl Menem was the first child of Syrian immigrants Saud Menehem and Mohibe Akil, who owned a store and had two other children, Munir and Eduardo. His surname was “Spanishized” by Migration. Carlos Menem attended primary and secondary school in La Rioja. In Córdoba, he studied law, and in 1958, he entered politics. He founded the Populist Party and was appointed as the interventionist of the Peronist Youth of La Rioja. In 1964, he traveled to Syria, where his family, the Yoma Gazal family, originated, to find a wife.

He visited Juan Domingo Perón in Spain, representing the Peronist Youth of La Rioja. Upon returning to La Rioja, he opened a law office with his brother Eduardo. In 1966, he married Zulema Yoma, with whom he had two children: Carlos Saúl (1968-1995), who died in a plane crash, and Zulema María Eva (1970). In 1972, Menem participated in the chartered flight that brought Perón back from exile to Argentina for the first time.

“Salariaço” and the Productive Revolution

His alignment with the Peronist Youth and his popularity in La Rioja allowed him to lead the provincial Peronist ticket and, in 1973, he became the youngest governor of Argentina. On March 24, 1976, he was arrested. Confined in the province of Formosa, he had a romantic relationship with María Elizabeth Meza, with whom he had a son, Carlos Fair.

In 1981, he was released, and in 1983, he was elected governor of his province. In 1985, he joined the Renewal Front of Peronism, and in 1988, he was chosen as a presidential candidate for the elections, which he won the following year with almost 50% of the votes. Due to the severe economic and social conflicts faced by the Radical government, Menem assumed the presidency five months early following the resignation of Raúl Alfonsín.

His electoral promises included the “salariaço” (salary boost) and a productive revolution. The situation in Argentina was critical: there was hyperinflation and looting of businesses. Menem formed an alliance with the country’s largest private company, Bunge y Born (BB Plan), to whom he handed over the Ministry of Economy through Néstor Rapanelli. Domingo Cavallo was appointed as the Minister of Foreign Relations. The conservative liberal Álvaro Alzogaray was appointed as an adviser, and his daughter María Julia was given important positions.

With these alliances, Menem reversed the historical tradition of Peronism. In line with the neoliberal policies of U.S. think tanks, he initiated the first wave of privatizations. Discontent from the Peronist left was expressed in the split of the General Confederation of Labor (CGT) and lawmakers.

In 1989, Menem granted a series of pardons to military officers convicted of human rights violations during the last dictatorship. Despite social backlash, he pardoned the high-ranking military officers (Jorge Rafael Videla, Emilio Massera, and Roberto Viola), the ideologue and leader of the Falklands War (Leopoldo Galtieri), and the leaders of the “painted-face” uprisings during Alfonsín’s government. The leaders of the Montoneros, Mario Firmenich and Roberto Vaca Narvaja, were also pardoned.

His alliance with the establishment sparked ultranationalist passions, such as the uprising of Colonel Mohamed Alí Seineldín, who denounced the neoliberal shift of the government and the unfulfilled electoral promises. The rebels were suppressed and arrested. In 1990, Rapanelli resigned and was succeeded by Antonio Erman González, one of Menem’s most loyal allies. That same year, the Supreme Court was expanded from five to nine members, resulting in an “automatic majority” of five judges appointed by the government.

In early 1991, the BB Plan began to show its failure: between December 1990 and January 1991, a new period of hyperinflation emerged. The Ministry of Economy was entrusted to Cavallo, who implemented the Convertibility Plan, which pegged the Argentine peso to the U.S. dollar. This reiterated the idea of José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, the Minister of Economy during the dictatorship: a cheap dollar as a guarantee for foreign investments; a currency parity policy, which would be maintained by selling public assets or taking on more foreign debt. In 1993, the “Menemism” won the midterm legislative elections, granting Peronism unquestionable hegemony.

Neoliberalism and Re-election

Menem proposed a constitutional reform to allow re-election in the 1995 elections. Thus, the Olivos Pact was formed between Menem and the main opposition leader, Alfonsín. This agreement involved accepting the constitutional reform in exchange for certain requirements demanded by the Radical Party, such as reducing the presidential term to four years, establishing a second-round electoral system, transitioning to a semi-parliamentary system to weaken the presidential system, and granting positions to Radical judges on the Supreme Court. In 1992, fundamentalist terrorism struck Argentina: first, with the attack on the Israeli Embassy—thirty killed—and later, in 1994, the attack on the Argentine Jewish Mutual Association, with 85 dead. Menem was re-elected in 1995 with 51% of the vote against the ticket of the Front for a Solidary Country (Frepaso), composed of José Octavio Bordón and Carlos Álvarez. At that time, Argentina reached its historical unemployment rate: 18%. The terrorist attacks were seen as a consequence of Menem’s foreign policy: the cycle of “carnal relations” with the United States and international financial organizations. Menem sent troops, against the majority’s will, to the Gulf War. In line with this strategy, he sought to restore diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom after the Falklands War. Within the context of regional economies, Menem’s first period was marked by the Mercosur treaty, which, with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, came into force on January 1, 1995.

Discontent with the repercussions of the Convertibility Plan (recession, unemployment, and poverty) led to significant opposition, headed by Frepaso. After overseeing the most extensive privatization and opening of the economy, Cavallo left the government amid a strong controversy with the state-owned postal service businessman Alfredo Yabrán, who was linked to the government. Nothing was left to privatize: oil, communications, transport services, water, electricity. The Argentine economy became “foreignized”: of the 530 major companies, more than 350 were foreign.

Associations organized two successive general strikes. In a context of growing corruption—the most notable cases being the illegal sale of weapons to Ecuador and Croatia and the computerization of the National Bank by IBM—Menem sought his “re-election.” In the 1997 legislative elections, the government’s significant defeat ended the officialdom’s dominance and revitalized opposition parties (Radicalism and Frepaso), which united in a coalition, the Alliance. Historical Peronism, represented by the governor of Buenos Aires, Eduardo Duhalde, and neoliberal Peronism, represented by Menem, clashed until the rupture. Both vied for the 1999 presidential succession. The murder of photographer José Luis Cabezas in January 1997 and the teachers’ protest, which established a peaceful encampment in front of Congress for over a thousand days, ended Menem’s “re-election” ambitions.

Defeat to Radicalism

In 1999, the UCR-Frepaso Alliance won the presidential election with 48.5% of the votes. Menem was detained—and soon released—during a judicial investigation into the illegal sale of arms to Ecuador and Croatia. In 2000, he married Chilean television presenter Cecilia Bolocco, with whom he had a son, Máximo Saúl, in 2004. With legal cases pending for illicit enrichment, in 2005, Menem spent most of his days in Chile.

The former president was elected senator in 2005. In 2013, at 82 years old, he was sentenced to seven years in prison for smuggling arms to Ecuador and Croatia, violating international embargoes in place during the 1990s. He was not imprisoned, however, as the Argentine Congress upheld his immunity.