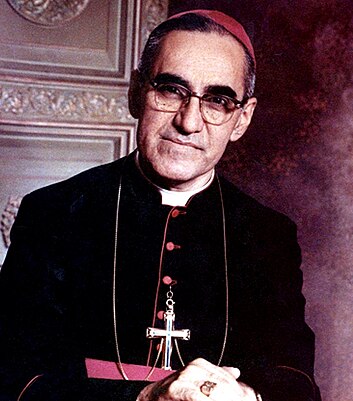

Ciudad Barrios, 1917 – San Salvador (El Salvador), 1980

By María Alicia Gutiérrez

The case of Monsignor Oscar Arnulfo Romero, martyr of the Catholic Church in El Salvador, is among those who took on, in their ecclesiastical role, the defense of the poor and, therefore, not without contradictions, the religious and political participation of their subordinates.

Born on August 15, 1917, Arnulfo Romero was ordained a priest in 1942 and began an intense pastoral action in various dioceses across his country. In the early 1970s, he began to embody the principles of the Second Vatican Council and the Medellín Conference by defending the “option for the poor.”

At that time, influenced by Liberation Theology, Base Ecclesial Communities began to multiply throughout Salvadoran territory, mobilizing against an oppressive regime. The response from official forces was swift: the assassination of religious leaders, torture, threats, and extortion.

In 1974, Father Romero denounced the brutal repression against the peasantry by sending a letter to the president of the Republic. Three years later, he was appointed bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, at a time when threats and murders by death squads against Catholic priests were on the rise. In light of the worsening political crisis, Bishop Romero became the principal denouncer of abuses and violence committed by security forces throughout the territory.

In his last homily, he synthesized the feelings of the marginalized, persecuted, and repressed. He concluded with an appeal to the members of the Army and security forces not to kill the peasants: “Brothers, they are of our same people; you are killing your own peasant brothers, and in the face of an order to kill that a man gives, the law of God must prevail, which says: ‘Thou shalt not kill’ […]. No soldier is obliged to obey an order against the law of God. An immoral law, no one has to comply with it. In the name of God and this suffering people […], I ask you, I beg you, I command you in the name of God, cease the repression.”

On March 24, 1980, Arnulfo Romero was assassinated by a gunshot to the heart while celebrating Mass in the chapel of the Hospital of Divine Providence.

He was aware of the risks he faced. Shortly before, he had survived a failed assassination attempt at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The resentment against his pastoral option was evident in the newspapers and in slanders and anonymous threats against his physical integrity. Sectors of big capital, fascist military figures, Roberto D’Aubuisson, leader of the Salvadoran death squad and founder of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA), and some conservative bishops and priests spread these slanders. They even reached Pope John Paul II, who “reprimanded” Romero for the vehemence of his words. In 1980, he met with the pope in Rome, providing him with reliable information about the terrible situation in the country. Additionally, he sent a letter to Jimmy Carter, the President of the United States, asking him to stop military support for the repressive forces of the Salvadoran government.

Dubbed “the voice of the voiceless,” he received significant international recognition: in 1978, he was named a doctor honoris causa by Georgetown University; in 1979, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize; and in 1980, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Louvain.

The greatest tribute the Salvadoran people could pay him was the massive attendance at his funeral, filled with peasants, workers, the marginalized, and even some elite families who held affection for him. Along the route, a strong crackdown left more than thirty dead and about three hundred injured.

The investigations of the Truth Commission, carried out by the United Nations, identified the intellectual authors and those responsible for Romero’s assassination as former Major Roberto D’Aubuisson and Captain Álvaro Saravia. Saravia was found guilty of the assassination in late 2004, in a civil trial held in California. However, in El Salvador, an amnesty law left this and many other atrocities unpunished.