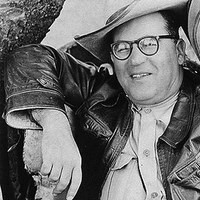

Cordisburgo, 1908 – Río de Janeiro (Brasil), 1967

By Flávio Aguiar

He lived between the two world wars, amid successive crises stemming from the decline in coffee production and political and educational transformations in the country. His literary universe expanded into a broad collection, recognized among the regionalists of realist prose like José Lins do Rego, openly leftist authors such as Jorge Amado, Abguar Bastos, Dionélio Machado, and Graciliano Ramos, and those ideologically centrist, like Marques Rebelo, João Alphonsus, and Ciro dos Anjos, who renewed writing forms from the 1930s onward.

Within this spectrum, the writer, according to critic Alfredo Bosi, created one of the branches of modern Brazilian regionalist fiction, one that “universalizes messages and ways of thinking of the sertanejo through an exploration into the core of its meanings.” He reclaimed the tradition of regionalists Afonso Arinos, Valdomiro Silveira, and Simões Lopes Neto, revolutionizing and transcending it in search of the metaphysical roots of literary creation. His first book of short stories, Sagarana (1946), was marked by a profusion of linguistic experiments later developed in Corpo de baile (1956).

In 1965, he attended the Congress of Latin American Writers in Genoa, where the First Society of Latin American Writers was founded, of which he served as vice-president alongside Guatemalan indigenous writer Miguel Ángel Asturias, a kindred spirit for his appreciation of popular culture. In 1961, he received the Machado de Assis Prize from the Brazilian Academy of Letters (ABL) for his body of work. In 1967, he saw the consolidation of his international recognition when his German, French, and Italian publishers considered nominating him for the Nobel Prize in Literature. His death, caused by cardiovascular complications at age 59, interrupted the award nomination process.

Shortly before his death, he accepted a chair at the ABL, a decision delayed since 1965 due to a premonition that something tragic would accompany his entry into the gallery of the “immortals.” History confirmed the premonition. His deep belief in the mystical powers of language permeates the metaphysical conception of his books, as seen in the themes of a devilish pact and the battle between good and evil, where each blends into the other, in Grande sertão: veredas (1956), his most well-known and ambitious work, with unforgettable characters like the former gunman and narrator Riobaldo, the leader Joca Ramiro, the volatile Zé Bebelo, the malevolent Hermógenes, and the enigmatic Diadorim.

By renewing the structure of narrative, as Clarice Lispector, Jorge Luis Borges, and José María Arguedas did, he broke with conventional genre boundaries and revitalized prose with lyricism and drama. After a vast inventory of sertanejo dialect and popular culture, he published Tutameia: terceiras estórias (1967), which greatly perplexed critics by creating a highly modern text from old traditions.

His innovative language delves into the preconscious dimensions of the jagunços (hired gunmen), children, the mad, and marginalized characters situated in a mythical time and place, bringing him closer to authors inclined toward magical realism, such as Alejo Carpentier and Gabriel García Márquez, or the fantastic, such as Murilo Rubião and Julio Cortázar, although with varied styles. Other works include: Primeiras estórias (1962); Estas estórias (1969).