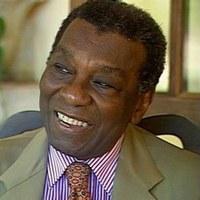

Brotas de Macaúbas, 1926 – São Paulo (Brasil), 2001

By Carlos Walter Porto-Gonçalves

In France, he was a professor at the universities of Toulouse (1967-1968) and Paris (1968-1971). He taught at the University of Toronto (1972-1973) and, in the United States, at Columbia University, New York (1976-1977), and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He also worked as a professor in Tanzania, at the University of Dar es Salaam (1974), and in Latin America, he taught at the Polytechnic University of Lima, Peru, and at the Central University of Caracas (UCV), Venezuela (1975-1976).

Upon his return to Brazil, he worked at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), at the University of São Paulo (USP) from 1978 to 1982 in the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism, and from 1983 to 1996 in the Department of Geography, before finally returning to the Federal University of Bahia in 1996. He was also a guest professor in Japan. His vast body of work, with hundreds of published articles and books, and his intellectual qualities, including his rejection of any dogmatism, earned him international recognition. Universities such as Toulouse (1980), Buenos Aires (1992), and Barcelona (1996) – to mention only those outside Brazil – awarded him honorary doctorates. In 1994, he received the Vautrin Lud Prize, considered the Nobel of geography, and it was the first time it was awarded to an intellectual whose native language was not English.

Spatial Formation

In Milton Santos’ writings, three dimensions are intertwined: theoretical-methodological, empirical, and ethical-political. Works like Por uma Geografia Nova (1978), Espaço e Método (1985), and A Natureza do Espaço − Técnica e Tempo / Razão e Emoção (1996), among others, have a more theoretical-methodological nature. The empirical dimension dominates in A Cidade nos Países Subdesenvolvidos (1965), O Espaço Dividido (1979), and O Brasil: Território e Sociedade no Início do Século XXI (2001). Among the works of a more ethical-political character, O Trabalho do Geógrafo no Terceiro Mundo (1970), Pensando o Espaço do Homem (1982), O Espaço do Cidadão (1987), Por Uma Outra Globalização − Do Pensamento Único à Consciência Universal (2000), and O Papel Ativo da Geografia: Um Manifesto (2000) stand out.

Note that, at times, the author gives the title of “manifesto” to important theoretical works. Such is the case, among others, with Por Uma Geografia Nova and explicitly with O Papel Ativo da Geografia: Um Manifesto.

In his writings, Milton Santos made a decisive contribution that helped place geographic space at the center of the debate about the dilemmas of contemporary society. For the author, society, technical objects, information, and communication increasingly involve nature. In this way, a complex space is configured, distinct from economic space, social space, or any other thematic space in a specific field of knowledge.

For Milton Santos, the idea of a system, in which the elements of a given situation depend on each other, refers to the category of totality. Only in this way – says Santos – can we move from “abstract empiricism, that is, the value given to things in themselves, to reach empirical abstraction, that is, a generalization that starts from what actually exists and is not merely a product of our imagination.”

The banal space of everyday life, a place of the coexistence of diversity, must be seen in its systemic connections with the totality, for which Milton Santos reinvented, in his work Por Uma Geografia Nova, the Marxist category of social formation as spatial or socio-spatial formation. The author acknowledges his debt to Marx but warns us that we must, by ourselves, “rediscover the materials, which are not the same as those of Marx, but those that allow me to produce ideas about what exists in the so-called real world. And so, we return or arrive at history, the immortal foundation of Marx’s method.”

This real world he speaks of is far from positivist empiricism, as what exists also involves the process of “becoming.” This is what places us in front of the future, not by voluntarism, but by what is inscribed in the world itself as latency.

Transformative Action

Milton Santos’ geographic space is a space-time for which periodization becomes central as a theoretical-methodological foundation. Here, once again, periodization is imposed, at the same time, as a scientific and ethical imperative, as only the identification of what is new, of what is different within a spatial-temporal process, allows for transformative, playful action.

This firm methodological concern with periodization allowed the author to avoid ideologized analyses of globalization, both affirmative and critical ones. Where some saw the end of history and others the same old imperialism, Milton Santos saw a historical period in which new situations emerged. Despite his concern with national issues of social inequality and underdevelopment, he never allowed himself to be carried away by superficial nationalist ideology. The unfolding of spatial social formation linked to the national issue, towards the technical-scientific-informational environment and the systems of objects and actions, was due to his constant attention to the transformations our world is undergoing. The socio-spatial formation of contemporary capitalism, as a technical-scientific-informational environment, shifts the place of the Nation-State in the new geographic and political configuration. Politics acquires a new meaning in the world and in Milton Santos’ work. Hence, the need to distinguish between the scale of the execution of actions and the scale of their direction. This distinction becomes fundamental in today’s world: many actions carried out in a specific place are the product of external needs, of functions generated far away, and only the response is located in that precise place. These are the verticalities that come into contradictory tension with the banal space where the coexistence of diversity, of horizontalities, and of the “strength of place” is found.

In characterizing the current period, the author surprises those tempted to see only the domination of imperialism in its new phase. Where verticality (the power of “those above,” “those from outside”) seeks to command through increasingly rapid instrumental rationality, there is a horizontality in which counter-rationality develops, even through the slow time of those who reside, not just pass by, or those interested only in a single dimension, the economic one, or rather, profits. Places are spaces of the multidimensionality of life, where the coexistence of diversity challenges everyone; they are the refuge that shapes each individual’s subjectivities.

Here we see the contradictions of the world presenting themselves with new qualities, and places gaining all their strength, as can be seen in events such as September 11, 2001, or the Argentine crisis of December 2001. The images of planes crashing into buildings or crowds banging pots and blocking streets show the full tension between verticalities and horizontalities, between, on one hand, those who act from afar, manipulating information, and on the other, ordinary people, social movements, and the poor.

Milton Santos’ identity with the problems of his time, especially his solidarity with those suffering the effects of what he called the “perverse globalitarian process,” was such that the title of one of his last books (Por Uma Outra Globalização), published before the 2000 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, could not be more aligned with those living forces seeking social justice, sovereign decision-making, environmental protection, and the right to be different, with radical democracy.

That same year, despite being weakened by illness, he insisted on attending the XII National Meeting of Geographers, held in July in Florianópolis. There, he actively participated in the AGB meetings, the entity that had propelled him into prominence across Brazil and the world. He passed away less than a year after the event.

Content updated on 05/19/2017 18:38