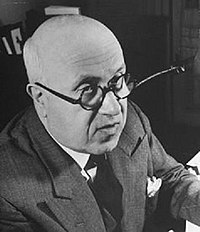

Montevidéu (Uruguai), 1880 – 1969

By Gerardo Caetano Hargain

Amid attempts to found a Socialist Party in Uruguay during the 1890s and the early years of the 20th century, Emilio Frugoni’s incorporation into the ranks of socialism marked a milestone in the entire process. Born into a wealthy family, with a father who was a merchant of Genoese origin, Frugoni’s first political activism took place within the ranks of the Colorado Party. He had a brief participation on the government side during the 1897 revolution; he was an organizer, along with José E. Rodó and Carlos Reyles, of the Colorado Club Liberdade, and returned to take part on the officialist side in the 1904 revolution, first enlisting as a national guard and later serving as an aide in the General Staff. This second experience as a direct participant in a civil war had a strong impact on his political convictions, leading to his distancing from the Colorado ranks and reorienting his ideas toward socialist proposals. By then, he was already a respected man in Montevideo’s intellectual circles: an advanced law student, poet, and polemicist. In the second half of 1904, he appeared as a member of the Socialist Workers’ Center, an institution that organized a public conference entitled Socialist Profession of Faith on December 22 of that same year at the headquarters of the New Star of Italy.

In 1910, Frugoni became the first Socialist Party deputy following that year’s elections, held within the framework of a coalition with the Liberal Party. He became a fundamental figure in Uruguayan political and cultural life: serving multiple terms as legislator between 1911 and 1942; a constituent in 1917; the first professor of Labor Legislation at the University of the Republic; Dean of the Faculty of Law between 1932 and 1933 (a position from which he, along with students, resisted the 1933 coup d’état); plenipotentiary minister of Uruguay to the Soviet Union between 1944 and 1946; journalist, poet, and essayist; author of numerous ideological, political, and literary works; and secretary-general of his party for decades, among many other notable aspects of his life.

As the undisputed leader of the Uruguayan Socialist Party from its foundation until the 1950s, he promoted a socialism with a liberal character, Atlanticist, strongly critical of the traditional Uruguayan parties, European-inspired in its main influences, critical of the Soviet experience (he faced the nascent communists defending Leninist theses in 1920 and 1921, when he was defeated), and a firm advocate of the necessary reconciliation between socialism and democracy. As the author of numerous doctrinal books and a true socialist ideologue, he lost hegemony within his party by the late 1950s. In 1962, he broke with the Socialist Party, rejecting its ties with factions split from the National Party in the brief and frustrating experience of the Popular Union. He then founded the Socialist Movement, under whose banner he ran again in the 1966 elections in a coalition with the Socialist Party. By that time already in his eighties, he did not hesitate to sell his famous library so his movement could finance an electoral campaign that ended in a harsh defeat. He passed away in August 1969, aged 89, proscribed like his party, when Uruguay was beginning to enter the dark times of authoritarianism. Carlos Quijano honored him with the following words:

“[…] no one can take away from Frugoni his honorable place in the history of the continent, […] the country […] socialism. A master of life and […] hope, he taught us by his example to persevere without triumphing: the virtue of pride and the value of modesty. Frugoni also taught us that Marxism […] is the only fruitful humanism and the highest idealism. And he revealed to us how love for the land and its people can be both a wound and a joy. […]”