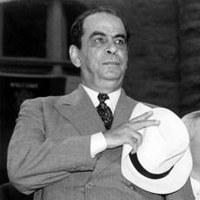

Caracas (Venezuela), 1884 – 1969

Margarita López Maya

Dom Rómulo Gallegos, as he was always called during his lifetime, was the first president elected in direct, universal, and secret elections in Venezuela. This occurred during the period known as the Adeco Triennium (1945–1948), when the Democratic Action party (Acción Democrática, AD) came to power for the first time through a civic-military coup known as the October Revolution. Gallegos had previously held several political positions. During the Gómez dictatorship, he left the country between 1931 and 1935, residing in Spain. He returned after the death of Juan Vicente Gómez, and during the governments of López Contreras and Medina Angarita, he served as Minister of Public Instruction (1937), deputy in the National Congress (1937), and councilor of Caracas (1941 and 1942). In 1941, he was one of the founders of AD. That same year, opposition forces to the “Andean” governments launched his candidacy for the presidency of the Republic. This was a symbolic act since, at the time, those forces were not in a position to compete for power under a regime with limited political freedoms. Gallegos then represented, and from then on, the struggle of those who aspired to the establishment of a democratic political system in Venezuela.

After the election of the Constituent Assembly and the approval of the 1947 Constitution, Gallegos was nominated for the presidency of the Republic, winning with a percentage still unmatched by any other candidate: he received 871,752 votes (73.6%) out of a total of 1,183,764. His government was very brief. In an international context characterized by the Cold War, the “radical democracy” exercised by AD during those years was seen as a nuisance by the United States government. Nationally, the intense mobilization and popular organization driven by the adecos within the labor, peasant, and student movements also created tensions among the civilian elites, as well as within sectors of the Armed Forces that had supported the revolutionary project since 1945. The combative style of political action irritated opposition parties, most of which backed the coup. The president was overthrown on November 24, 1948, in a coup d’état supported by the entire Armed Forces and led by his own Minister of Defense. On December 2, he wrote a Manifesto to the Nation in which he made it clear he had not resigned. Three days later, he was expelled from Venezuela. Upon setting foot on Cuban soil, en route to Mexico, he gave statements pointing out the presence of the U.S. military attaché at the Miraflores Palace on the day of the coup. He returned to the country after the fall of dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez in January 1958.

Gallegos also had a notable career as an educator. He was director of the Federal College of Barcelona (Anzoátegui State), the Normal School of Caracas, and the Federal College of Caracas between 1922 and 1930. The latter was known as Liceo Caracas and later renamed Liceo Andrés Bello. There, he trained a generation of future Venezuelan politicians of the 20th century such as Rómulo Betancourt, Jóvito Villalba, Miguel Otero Silva, Raúl Leoni, Isaac Pardo, among many others, of whom he was a teacher. With many of these young men, he founded the Democratic Action party.

However, above all else, Gallegos was a writer and novelist, achieving prominence as one of the most important literary figures of Latin America in the 20th century. He founded literary magazines and weekly journals in Venezuela, where his first essays and stories appeared, but his literary work, especially his novels, quickly gained recognition in the Spanish-speaking world. His most important and famous works were written in Spain during his self-imposed exile: Doña Bárbara, Canaima, and Cantaclaro. Other well-known novels include Pobre Negro, Sobre la misma tierra, El Forastero, Reinaldo Solar, and El hilo de palama en el viento. These works always carried moralizing purposes, but the best of his prose emerged when this goal faded and the novelist allowed himself to be carried away by his creative genius, talent, and passion for fiction. The struggle between good and evil — and between civilization and barbarism — depicted in Doña Bárbara, set in the Venezuelan plains, made him famous at a time when capitalist modernization forces were vying for dominance in the region. He received the National Literature Prize (1957–1958) and joined the Venezuelan Academy of Language (1958). In 1965, in recognition of his career and fame, the Venezuelan state created the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize, and in 1972 founded the Rómulo Gallegos Center for Latin American Studies (CELARG). The Center’s headquarters in Caracas is built on the land where his house once stood — the place from which Dom Rómulo Gallegos left for exile in 1948 — and where he died in 1969.