Núcleo de Estudos em Tribunais Internacionais

Faculdade de Direito

Universidade de São Paulo

Largo de São Francisco, 95

Sé – São Paulo, SP

01006-020

On Wednesday, 16 June, a new Prosecutor was sworn in at the International Criminal Court (ICC). Karim Asad Ahmad Khan QC was elected to this position by the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute (ASP) on 12 February 2021 at the second resumed nineteenth session. The first, held in December 2020, failed to elect the new ICC Prosecutor.

Following Luis Moreno Ocampo (2003-2012) and Fatou Bensouda (2012-2021) – who previously served as Deputy Prosecutor during Ocampo’s term –, Khan is the third ICC Prosecutor.

While Bensouda represented a continuation of the previous administration of the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), Karim Khan gives us hope of much-needed new guidance. Khan is an international criminal lawyer and has worked in the past years as a Special Adviser and Head of the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes committed by ISIL (Da’esh) in Iraq (UNITAD). He has acted as counsel at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) and the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL). At the ICTY and ICTR, Khan was respectively a legal adviser and officer at the OTP.

The work that lies ahead for Karim Khan is not easy. This year alone, Bensouda concluded preliminary examinations and requested investigations on two situations that will prove a challenge to the ICC: the first is Palestine, which investigates crimes committed by Israel, Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups; and the second is the Philippines, which took place two days before she left office and has the purpose of investigating the Government of Philippines “war on drugs” campaign. Not to mention the investigation into Afghanistan, which already has proved a challenge for the ICC.

Let’s look at the OTP’s activities[1] that lie ahead for Mr Khan.

Preliminary examinations

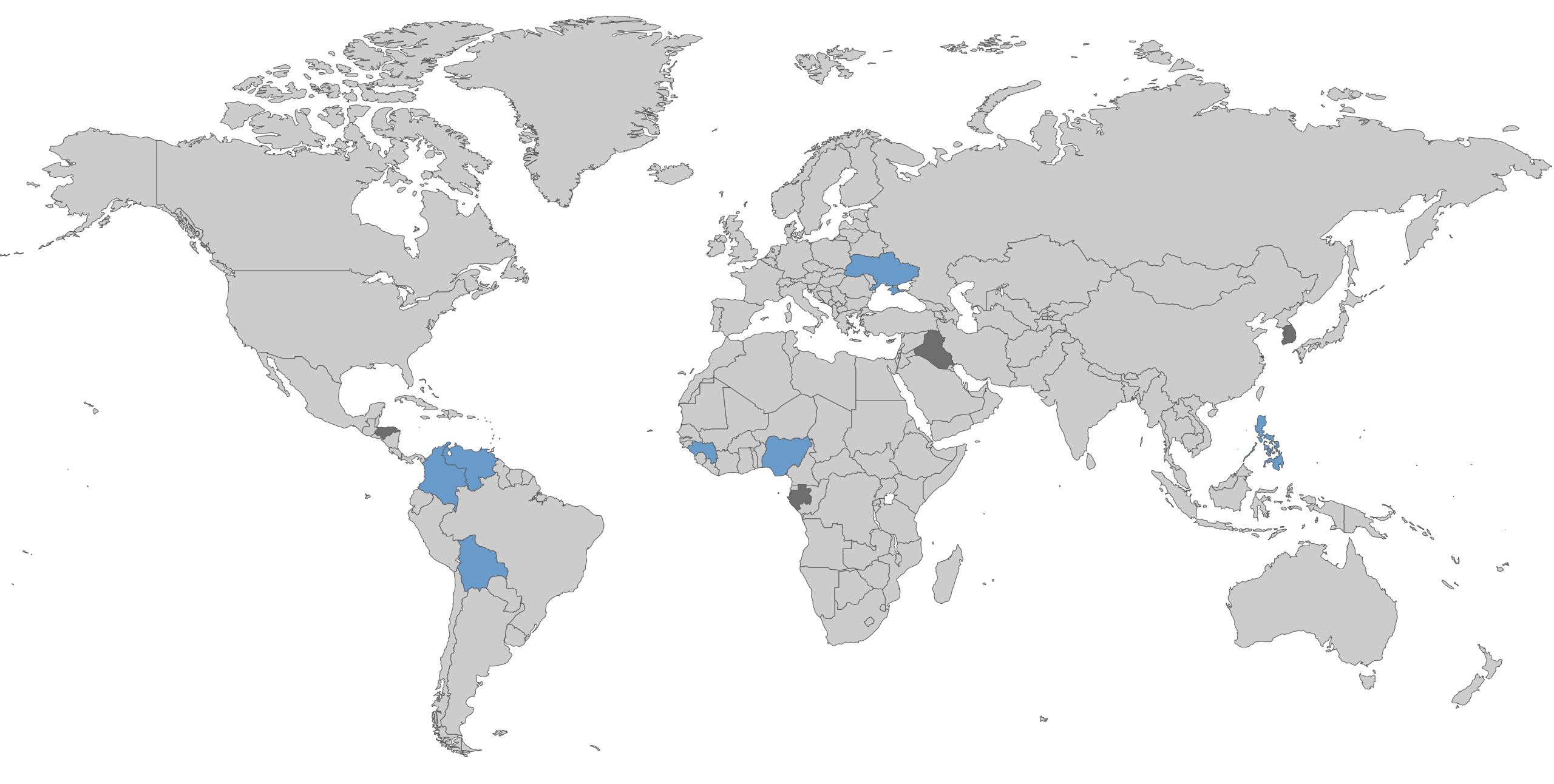

There are currently nine situations under phases one and two of preliminary examinations.

Phase 1 comprehends the examinations that are going through the initial assessment of the allegations received through communications under article 15 of the Rome Statute. At this stage, the OTP verifies the information, filters out the crimes not under the Court’s jurisdiction while checking whether there are crimes that fall within its jurisdiction. Even though the focus of Phase 1 is on subject-matter jurisdiction, its “assessment may also consider questions of gravity and complementarity where they appear relevant.”[2]

Phase 2 marks formally the beginning of preliminary examinations. For situations not triggered by article 15 communications – information arising from referrals by a State Party or the Security Council, declarations lodged under article 12(3), and testimony received at the Court –, this is the first stage of proceedings. During this phase, the OTP analyses “whether the preconditions to the exercise of jurisdiction under article 12 are satisfied and whether there is a reasonable basis to believe that the alleged crimes fall within the subject-matter jurisdiction of the Court.”[3]

Two situations are under Phase 2: Venezuela II and the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

No longer looking if whether the crimes in question are within the Court’s jurisdiction, in Phase 3, the admissibility examination is carried out. During this proceeding, two criteria are under scrutiny: complementarity (article 17(1)(a-c)) and gravity (article 17(1)(d)).[4]

The idea of complementarity is that States have a primary responsibility to exercise criminal jurisdiction. Complementarity is an aspect of admissibility that sometimes causes confusion. The notion of complementarity does not imply the exhaustion of domestic remedies, a criterion generally used by international human rights courts. Complementarity presupposes verifying whether there is (or was) a trial for the situation in question at the national level. If it exists, the analysis of the OTP seeks to verify if any of the scenarios provided in article 17(1) are present.

The gravity criterion is a threshold to exclude cases considered to be of lesser significance. However, there is not a number of victims from which to establish whether the gravity threshold has been met. In the decision on the Admissibility Challenge raised by the Defence for Insufficient Gravity of the Al Hassan case, the Appeals Chamber stated that, while the quantitative aspect is relevant, it cannot be decisive in establishing the gravity of the situation. Therefore, this assessment must be holistic, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative elements. On the other hand, the qualitative components would be related to the nature of the crimes, the degree of responsibility of the perpetrator, the motives, etc. Thus, after evaluating the seriousness in its quantitative and qualitative aspects, the Court, despite having jurisdiction over the case and the fact that it meets the admissibility criteria, may not proceed with it, considering it to be less serious. The gravity assessment is perhaps the key to helping us understand that not every mass violation of human rights will be prosecuted at the ICC.

Three situations are under Phase 3: Colombia, Guinea, Venezuela I.

The final stage of preliminary examinations is Phase 4, in which the OTP assesses the interests of justice. This evaluation provides the basis for the Prosecutor to determine whether to initiate an investigation under article 53(1).

Article 53(1)(c) of the Rome Statute presents one last parameter for the preliminary examinations to be concluded: the interests of justice. This consideration was already discussed in a 2007 policy paper and presupposes the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to proceed or not with the investigation based on the facts and circumstances of the situation, even if all the other criteria have been met.

One situation is under Phase 4: Nigeria.

The preliminary examinations of the situations of Ukraine and the Republic of the Philippines already have already been concluded. The OTP has requested the Pre-Trial Chamber to open investigations for both situations, respectively on 11 December 2020 and 14 June 2021.

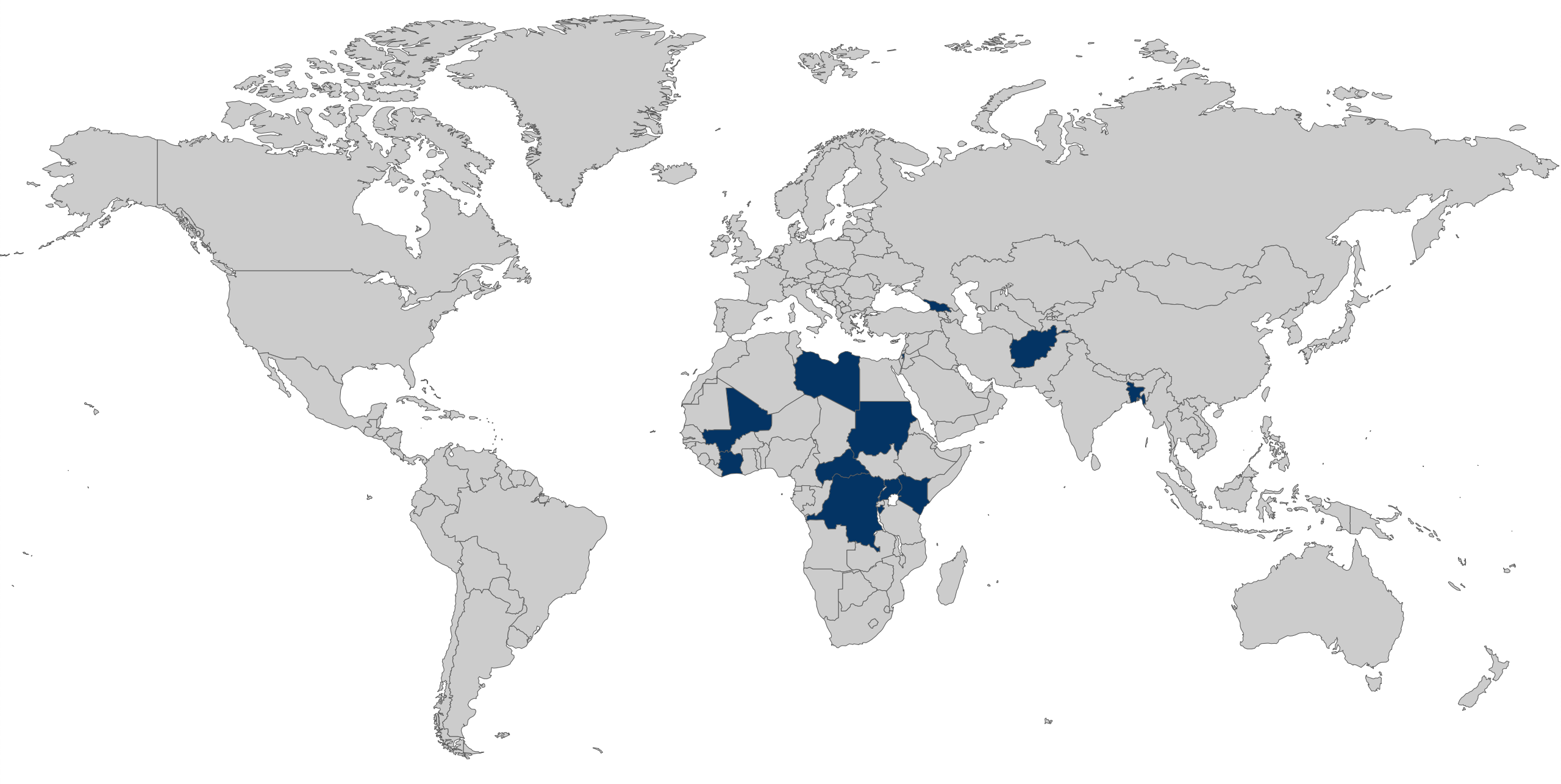

Investigations

During the investigations phase, unlike preliminary examinations, the Prosecutor enjoys the full range of investigative powers as conferred by article 54 of the Rome Statute. It is during this stage that the OTP makes a thorough analysis seeking to identify all the crimes that were committed and the individuals associated with them. “Once the OTP considers that it has sufficient evidence to prove before the judges that an individual is responsible for a crime in the Court’s jurisdiction, the Office will request the judges to issue a warrant of arrest or a summons to appear.”[5]

There are currently 14 situations under investigation:

Cases

Currently, the caseload of the ICC consists of 14 cases on Pre-Trial, 3 cases on trial, 1 case on appeal.

Cases on Pre-Trial are either under preparations for the trial to commence or waiting for a defendant at large to show or be arrested and delivered to the ICC.

Pre-Trial | |

Said Abdel Kani Case (in custody) | |

Gicheru Case (in custody) | |

Ali Abd-Al-Rahman Case (in custody) | |

Trial | |

Appeal | |

[1] The following information is based on the OTP’s 2020 Preliminary Examination Report, published in December 2020n and updated according to documents and information published on the ICC website.

[2] OTP’s 2020 Preliminary Examinations Report, para. 27.

[3] Office of the Prosecutor’s Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations, para. 80.

[4] Office of the Prosecutor’s Policy Paper on Preliminary Examinations, para. 42.

[5] https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp

Núcleo de Estudos em Tribunais Internacionais

Faculdade de Direito

Universidade de São Paulo

Largo de São Francisco, 95

Sé – São Paulo, SP

01006-020